Book Review: ‘Temple Economics’ by Sandeep Singh – A Guide of Historical & Modern Challenges to our “Nucleus” of Arthvyavastha

July 13, 2024

Book Review by Saumya Bhatt

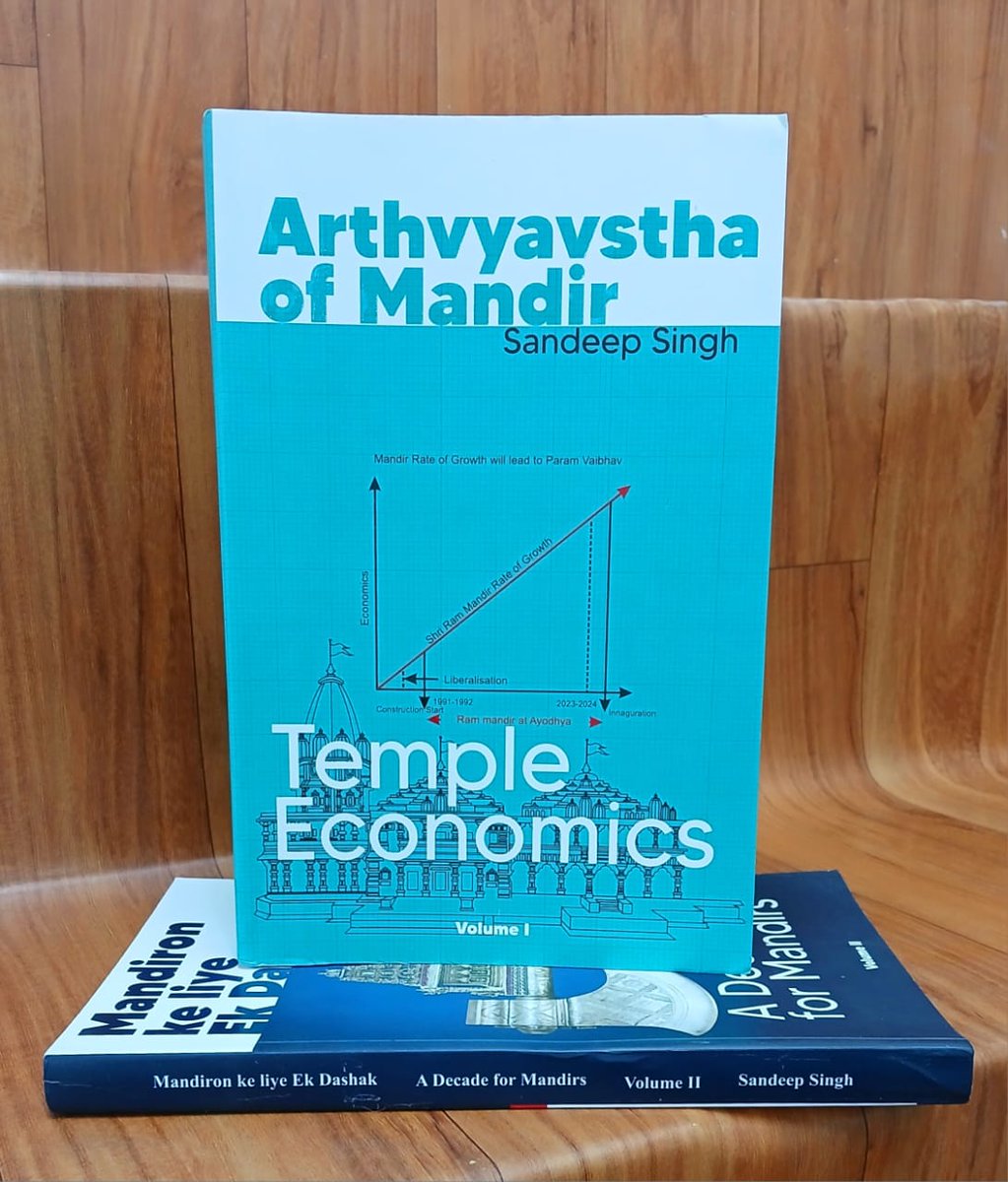

‘Temple Economics (Arthvyavastha of Mandir)’ is a meticulously researched book written by Sandeep Singh. This book(volume-1) delves into the historical and ongoing challenges faced by Hindu temples in India.

Singh outlines the destructive impact of historical invasions, colonialism, and modern secular governance on the Hindu temples and their wealth. He emphasizes how despite India’s independence in 1947, Hindu temples remained under the control of the secular government, facing various financial and administrative challenges.

The book gives examples to show how temples have historically been the “nucleus” of economic activity, cultural preservation, and community services. The inclusion of case studies and real-world examples helps to ground theoretical concepts in practical reality, offering valuable insights for temple administrators and policymakers. Singh examines how films, literature, and other cultural outputs have contributed to a negative perception of temples and Hindu practices. Specific examples from popular movies are cited to show how temples are often portrayed in a derogatory manner.

The book is a comprehensive exploration divided into four insightful parts:

Part-1 Arthashastra of Mandirs,

Part-2 Destruction of Mandir and its Arthvyavastha,

Part-3 Loss of Mandir Ecosystem, Post Independence, and

Part-4 Need to Reestablish Mandir Ecosystem.

Part-1: Arthashastra of Mandirs

Singh distinguishes between the terms “Mandir” and “Temple,” emphasizing that while temples are merely places of worship, Mandirs are the abodes of Bhagwan. According to Vastusilpakosa, a Mandir effectively utilizes the energy, talent, skill, and leisure of the community members.

This section delves into the various names for Mandirs, such as Alayam, Devalaya, Devagriha, and Kovil, and explains their classifications based on ownership, builder and location, building material, origin of deity, postures of deity, region and architectural styles, and scriptures.

A notable highlight in this part is that Mandir’s revenue is a subset of the Mandir-based Arthvyavastha. It explains how Mandirs served not only religious functions but were also centers of science, technology, philosophy, art, and education. They undertook social and civic duties and embodied “Dharma,” which encompasses natural behavior, duty, law, ethics, virtues, etc.

The concept of “Laabh,” or profit, is discussed in the context of “Shubh-Laabh,” implying that profit must be auspicious. Additionally in the book, the saree, a product of Arthvyavastha, is noted as having faced repeated attacks.

Mandirs were central to the Arthvyavastha and were often targets of invaders due to their power and influence. Cities developed around Mandirs, becoming vibrant hubs of knowledge, business, and social responsibility. The book also explores various facets of Mandir culture, including Karmakand Sanskar, Prasad, Shilpkala, Art, Parikrama, Tirthayatra, Mela, Matham, Sampradaaya, and Aadhyaatmic.

Part-2 Destruction of Mandir and its Arthvyavastha

In Part-2, Singh highlights the destruction by Islamic invaders, noting their systematic efforts to dismantle temples, aware that Hindus do not worship in temples without intact idols. The case study of Devi Ahilya Bai Holkar vs Aurangzeb showcases Hindu resilience in rebuilding temples.

The book also examines the Portuguese Christian invasion and secular invasion, revealing efforts to weaken Sanskrit and disrupt Hindu practices. The British recognized temples as centers of governance and economy, leading to their takeover of mismanaged temples, deemed an “absolute necessity” in 1838. A section also addresses the Bharat Halal Economy, detailing its impact on Hindu wealth through halal-certified products across various sectors, including food, cosmetics, medicines, and even prasad.

The attack on Kumbh Mela during the COVID-19 pandemic by international media, Indian media, Islamists, politicians, and multinational corporations is scrutinized, citing negative portrayals by outlets like National Geographic. This part also discusses how Britishers targeted Devdasis to control temples, distort Hindu practices, and facilitate conversions to Christianity, exploiting girls and creating societal divisions.

Part-3 Loss of Mandir Ecosystem, Post Independence

This section presents vivid descriptions and case studies, revealing how mandirs are losing their significance due to discontinued rituals, broken traditions, and diminished activities. It discusses the abuse of Pujaris, alienation and destruction of mandirs, and the discouragement and killing of devotees. The text identifies seculars, communists, and abrahamics as primary perpetrators of these actions. Additionally, it argues that Public Interest Litigation (PIL) and Right to Information (RTI) acts have catalyzed this destruction, with media and NGOs serving as tools, and politicians, judiciary, bureaucracy, and government executing the destruction.

Post-1947, the transfer of power marked a significant shift, with Nehru being the first politician to oppose mandirs. In 1959, he expressed his disdain, particularly for the temples of South India, stating that they oppressed his spirit and prevented him from rising.

The section also addresses the Sabarimala mandir, describing efforts to alienate the mandir, discourage devotees, and even attempts to kill devotees, again attributing these actions to seculars, communists, and abrahamics. It emphasizes that Hindutva respects menstruating women, citing ancient texts like Angirasa Smriti and Vashistha Dharmasutra that mention rest for women during menstruation. The text outlines three ways Bharat celebrates menstruation: worshipping Devi at Kamakhya mandir, worshipping Mother Earth in rituals like Keddasa in Karnataka and Raja Parva in Odisha, and celebrating girls attaining puberty.

This part also critiques the imposition of Western constructs on Hindus, using the “happy to bleed” and “#RightToPray” campaigns as examples. It contrasts these with the “Ready to wait” campaign, which aligns with Hindutva principles, highlighting the understanding and respect for traditions regarding women’s entry into the Sabarimala Mandir, and the willingness of women in Kerala to wait until they are 50 to enter the mandir.

Part-4 Need to Reestablish Mandir Ecosystem

In Part 4, Singh presents empirical evidence highlighting the economic benefits of temple-based economies on both government and private sectors. Government schemes like the Gangajal Delivery Scheme, Holy Blessings Scheme, Gold Sales, Railways’ Dharmic Yatras, Prasad distribution to self-help groups, sales for the Khadi Board and cooperatives, and the Gold Monetization Scheme all contribute to the revenue. The private sector benefits from the hospitality and travel industries, as well as online services related to temple activities.

A graph on the book’s cover page illustrates the projected growth rate of temple-based economies, leading to “Param Vaibhav” (supreme prosperity), with this part mentioning specific figures on the benefits of the Ram Mandir construction in Ayodhya.

Singh also compares temples to aircraft carriers, suggesting that just as an aircraft carrier defends a nation, a temple protects and nurtures “Desh and Dharma”.

The book covers the economic aspects, construction, and historical context of temples in Bharat in an insightful manner. It is a meticulously detailed piece, not just about the Mandirs and their related economics (as the title suggests), but also about all connected links, the ecosystem, and the larger picture which one can’t miss. Volume 2 focuses on how Hindus can reclaim and restore the glory of their temples.

Related Stories

Recent Stories

- Rahul Gandhi to be on Gujarat visit on April 15–16

- Bridge City Surat likely to get one more bridge on April 18th

- Former MLA Mahesh Vasava quits BJP

- Work begins on 1.3-km tunnel in Poshina for Taranga Hill–Ambaji–Abu Road rail project

- AUDA to repair 3 bridges on SP Ring Road

- Gabbar Hill darshan, Parikrama route, Ropeway to remain shut from April 15-17

- Western Railway to run Udhna–Danapur Unreserved Special Train